My History with Music Technology - Part 1

These pages will have an ongoing history of my involvement with music and art technology. It's based on some slideshows I did at various places around New South Wales in mid 2009. As I get more work converted to the proper formats, it will be greatly expanded with new material. Eventually, I hope this material will become part of a forthcoming book.

Part 1: The beginning:

The year is 1962. I'm sitting at my Aunt Billie's Hammond Organ in Windber, Pennsylvania. What I was playing undoubtedly didn't sound like this:

Bossa Blotto No. 1 (2004) (excerpt)

This is an excerpt from Bossa Blotto No. 1 from 2004. It's based on some midi-files of Bossa Novas from some Brazilian website which disappeared by the next time I went to it. As you hear, I pretty thoroughly messed around with the source material. While this is a 2004 piece, I was probably playing something like the introduction to the piece, and probably was wishing that I could make changes like the ones in this piece. What I WAS involved with at this point was what I like to call my "search for the weird." In high school, the closest I could come to that was a Messiaen record ("Trois Petite Liturgies") from the local public library, which had an Ondes Martinot on it - what was that sound???

Also, at that time, I was a listener to all night WNBC radio from New York City (we were 200km north of New York, so we could only get WNBC on AM radio at night. They had an all night talk show hosted by Long John Nebel, which had a theme song which also had electronic sound on it. And then, NBC on the weekends had a magazine-format radio show called "Monitor," which featured an electronic sting called "The Monitor Beacon."

That's the sound of the Monitor Beacon. Apparently, it was made with oscillators and tape recorders, and telephone dialling tones - real classic tape studio technique stuff. A couple of years ago, I acquired this sample, and used it in a couple of pieces as a reference to one of the sounds from my teen years that got me started on all this.

I was also "searching for the weird" in other fields as well - visual, poetic, performance, and only getting hints of them. In a bank in Albany, I saw a Franz Kline painting, which I instantly loved (and 42 years of reading anti-modernist art theory hasn't dimmed my love for Kline's work one bit), and as a teen-ager, my mom bought me summer tickets to the Saratoga Performing Arts Center's New York City Ballet seasons, so I saw all the Stravinsky-Balanchine collaborations in their repertoire. By the time I got to University in 1967, I knew there was a "weird world" out there to discover, and I was waiting for it.

Franz Kline painting, photographed Albany State Office Building Mall, 1979

1967-71 at the State University of New York at Albany

In my last few months of high school, I went to several Universities to check them out. At SUNY-Albany, I talked to a young guy named Joel Chadabe, and in his office was an early Moog Model 3 synthesizer (or was it 2 - it didn't have sequencers, so it might be a 2). I asked him "What's that?" He said "A synthesizer." I asked - "Will I be able to play with it." He said that yes, after the introductory music courses, I would indeed be able to take the electronic music courses. And then, with a twinkle in his eye, and the jolly humor I would come to know him very well for, he said, "But I've got to warn you, kid - the first one's free...." We both had a good belly laugh over that. He was right, of course - it was absolutely addictive. By mid-1968, I was indeed playing with the Moog, and learning tape splicing, and recording technology, etc. It was quite a fun time, and Joel was a great teacher. An example of his genial sense of humor can be seen in this portrait shot from 1971, as he hams it up as the vampire. In the background, by the way, are Kenneth Gaburo, Alan Johnson and Jack Logan, all from San Diego, and all whom I would later get to know quite well.

One thing I appreciated about Joel was his sense of the utter normality of what other people would consider weird. I remember in early 1968 the Contemporary Chamber Ensemble came to SUNY-Albany on a tour - one thing they were playing was the Elliott Carter Double Concerto. I was blown away by this piece - and Joel's reaction to the piece was something on the order of "Well, of course, that's what people are writing these days!" Not that it was exceptional - or the norm - it was just the way things were. There was no "religious zeal" for modernism - just a simple acceptance of what people were doing.

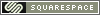

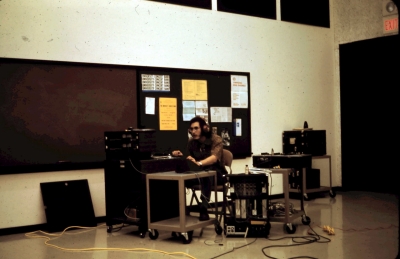

By 1970, Joel and SUNY took delivery of the CEMS system - what was at that time one of the largest Moog setups in the world. Here are two pix of Joel and the CEMS system - my friends and I at the time called it "Mother."

In the upper photo, you can see one of the banks of 4 sequencers, as well as the oscillators that the CEMS system had. In the lower photo, you can see the second bank of 4 sequencers behind Joel, and in the foreground is a digital clock Moog specially built for the system. It had 10 counters on it, and it could make very complex large scale rhythmic and structural patterns which could be sent through the patch bay to the oscillators and the sequencers.

One thing unique about this studio was that it didn't have a traditional style mixer. There were mixers on the Moog itself, and there were several reel to reel tape recorders on the other side of the studio (the photographer must have been sitting on them to get these camera angles), but the idea in this studio was to set up large-scale automated patches to make things, rather than to intensely splice and assemble things. That was done in the smaller studio, two rooms down the hall. I made several pieces with the CEMS system. One of them was "The Trilobite Trilogy Blues" which was a big multichannel tape collage. I assembled a number of reel to reel tapes with my favorite material - some by me (a lot of the chamber music quoted is from student instrumental pieces of mine), and some collected from many different sources. This, remember, was YEARS before all the controversy over sampling (samplers wouldn't be invented for another 8 or 9 years), and we were living in an environment where collage was a completely normal thing. Rauschenberg's collages were well known, and I was well acquainted with the collage technique of Charles Ives, and pop work with collage like Frank Zappa's. So it was no big deal to quote things. Here's the first minute of the piece.

Trilobite Trilogy Blues (1970-71) (excerpt)

I also became intrigued with the idea of using all those sequencers to make vast cycles of overlapping patterns which wouldn't repeat for a very long time, and to use those patterns to control the timbre of a single sound, evolving in time. After several attempts, my most successful realization of this idea was a piece called "Rain at Dawn; Late Autumn; Saranac Lake." It was a 15 minute tape piece, and with this piece, I felt that I'd really arrived at a point where I understood the technology and what it could do.

Rain at Dawn; Late Autumn; Saranac Lake 1971 (excerpt)

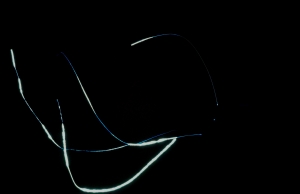

At Albany, I got interested in many things. Since the Moog was simply a big source of voltages and control, it seemed logical to many of us that that control could be applied to many different media, not just musical sound. For example, one could take the oscillators, and view them in an oscilloscope. By using the horizontal and vertical inputs into the 'scope, one could get changing diagrams called "Lissajous figures." Encouraged by film and video artist Tom de Witt, I made a piece with this technique - as I remember, it was about 80 minutes long, and was designed to function as an installation - on a video monitor in a corner of a museum somewhere. This never happened, and eventually, I converted about 10 minutes of it to videotape when I was in San Diego, but I believe the tape of this was lost. In any case, I have two stills from the piece. Here they are:

Warren Burt: Starship (1970-71) for video and sound. 2 stills.

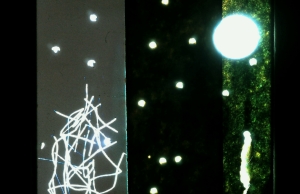

I also became interested in graphic notation, and various ways of converting images into sound. I began experimenting with scratching on film, with the idea that someday these slides could be converted into sound with some kind of a photocell-to-sound converter, or some kind of a visual scanner that could convert images into sound. It wasn't until 2009 that I managed to realize this idea, and a short video made with these 1971 images is now up on YouTube.

Warren Burt: Graphic Score, July 71, scratching on film

Warren Burt: Graphic Score Aug 71 - scratching on film, using slide material from the end of film rolls.

At this time, I was also involved in language, and was fascinated with the idea of crossing the divide between language and music. The CEMS Moog had 8 sets of control voltage gates, which could cut between 3 different voltages. These, I thought, could also be used for audio, specifically language. If there were some glitches from the cuts (because these were control gates, not designed for audio), all the better. As well, one could also process external sounds through a device called an envelope follower, which would trace the loudness curve of a sound, and this signal could control any other aspect of sound you desired. At this point, I discovered the anonymous Victorian pornographic classic "My Secret Life," and the protagonist Walter's endlessly re-iterated descriptions of his escapades seemed very close in spirit to the new musical style we were enthusiastically hearing about called "minimalism." I recorded 18 friends, each reading 5 minutes from the book (chief of which was my good friend R. Christopher Cooper), and then made a series of pieces with these recordings. Each of the series of pieces gradually revealed more and more of the language (the linguistic analog to a striptease?) until the erotic writing was fully revealed at the end. In the first of the series, "The Rhythms of Wattie," the voices are processed through the envelope follower, which controls oscillators. No words are heard, only the rhythm of the language.

The Rhythms of Wattie (1970)(excerpt from Trilobites and Aardvarks)

In the next piece, "The Aardvark's Icebag Meets the Incredible Kiwi's Buried Machine" the voices are chopped between with the switching gate, and the resulting chop-up is then ring-modulated. Some voices are heard, but only fragmentarily. There is just a hint of semantic content here.

In the final piece of the series "PornoCopia/PornoChop" the voices are heard unmodified, but still greatly chopped up. The piece starts with very rapid chopping, creating a babble of voice sounds. Gradually, over the first 2 minutes, things slow down, revealing more and more intelligible language, until the erotic narratives begin to reveal themselves. In this excerpt from the beginning, one hears t he babble, and towards the end, just the first hints of recognizable language. This is a family website, so we discretely fade out here, before too many "naughty words" are heard. Those slavering perverts among you out there who want to hear the whole thing (and enjoy its high-spirited erotic humor), may order the CD "Trilobites and Aaardvarks" Scarlet Aardvark CD 1, from this website.

PornoCopia / PornoChop (1971) (excerpt from "Trilobites and Aardvarks")

What some of the technology we used at Albany was, can be seen from a project my fellow student Randy Cohen did, called "Cymbals." Randy wanted to get complex timbres which changed constantly. He felt that for this piece electronic tones wouldn't provide the variability he needed. He decided that the sound of cymbals and gongs were very rich, and by moving a microphone over them, rich sweeps of changing harmonics could be obtained. The problem was to get rid of the attacks, the sound of striking the cymbals or gongs. The way this was done was with a hand-held microphone feeding into one of the Moog Voltage Controlled Amplifiers. This was controlled by another performer (me) with one of the Moog joysticks. Randy would strike the cymbal or gong, and immediately start moving the microphone. I would slowly fade in the volume on the mic after his hit, shaping a long attack on the cymbal sound. The output of this was recorded to 2 track tape. Later, Randy would edit these tapes and mix them together. The following four photos show how this process worked. Neither Randy nor I can remember who the photographer was. If you see these pictures, and remember that you took the photos, we'd love to hear from you. Randy, by the way, went on to a most interesting career. He was a writer for David Letterman for many years, wrote several books, and as of 2009 was writing "The Ethicist" for the Sunday New York Times Magazine.

Randy Cohen: Cymbals (1970-71) Randy moves microphone over cymbal to get changing spectra.

Randy Cohen: Cymbals (1970-71) Randy moves microphone near gong to get deeper changing spectra.

Randy Cohen: Cymbals (1970-71) Warren moves Moog joystick, controlling loudness shape of spectra.

Randy Cohen: Cymbals (1970-71) Warren recording shaped cymbal sounds. Note the back of the Moog portable module case on the floor in the center of the setup.

While we're at it, here's a photo of me playing accordion in the CEMS studio. The tape recorders can be seen in the background. I was taking the sound of my accordion, and running it through the ring modulator on the Moog, with the oscillators controlling the ring modulator being controlled by the multiple sequencers of the CEMS system, recording multiple tracks of that, and mixing it. This was for a piece called "The Mystical Dreams and Cosmic Vibrations of Elsie the Cow." I was never satisfied with the piece enough to perform it, or distribute it. Ring modulated accordion remains an idea I'd like to more fully explore someday.

Warren Burt in SUNY Studio 1970-71, recording accordion through ring modulator.

One of Joel's strategies for compositional education was that of apprenticeship. He was very active in organizing concerts, and inspired many of us to join in. He would introduce you to the visiting performer, and say to them that you were their assistant. And you would then help them in the setup and whatever else needed to be done for their concert. This was fabulous training, and professional networking. It showed us that the people whose work we were studying were just normal folks, and it showed us what was involved in putting on events competently. In the Spring of 1971, we organized a large set of concerts called FSTVL71. Three of the events in this festival were crucial for me - the performances by Kenneth Gaburo and his New Music Choral Ensemble III; the performances by Salvatore Martirano on his Sal-Mar Construction; and the multi-media extravaganza HPSCHD by John Cage and Lejaren Hiller, with a cast of thousands, as they say.

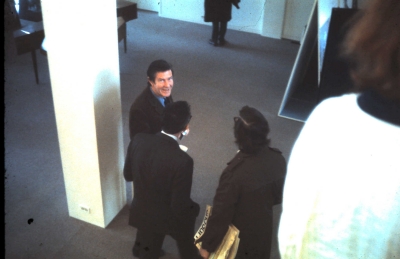

The visit of Gaburo and his group introduced me not only to Kenneth, but also the members of his ensemble, who were all grad students at UCSD, some of whom would become valuable colleagues and friends. And seeing as how I had already been working with works which crossed the language/music divide, and works which were dealing with scatological language, to see Gaburo's group do his Maledetto, for seven speaking voices, was absolutely inspirational for me. Here was indeed a kindred spirit. Here's a photo of Kenneth during the setup for the NMCE concert at the Art Gallery of SUNY Albany. He is contemplating where to position the film projector for his "Dante's Joynte," for tape, film and speaking/shouting dancers.

Kenneth Gaburo: Art Gallery, SUNY Albany 1971

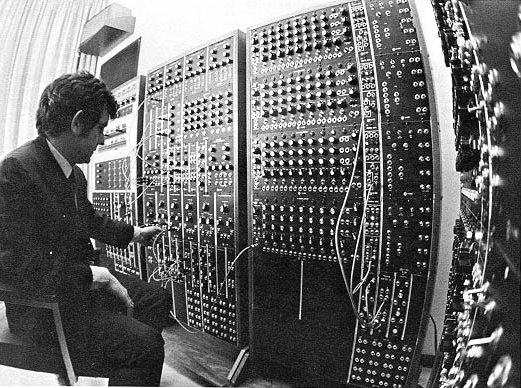

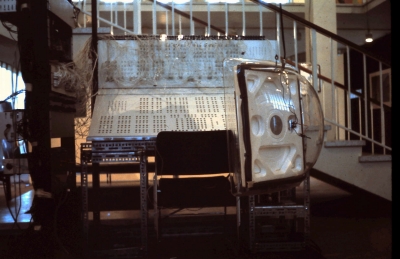

Another inspirational visit was that of Salvatore Martirano and his Sal-Mar Construction - a massive real-time hybrid digital/analog synthesizer that played out of an array of 24 or so suspended styrofoam loudspeakers. The product of several years building and research by Martirano and his collaborators at the University of Illinois, it showed me how powerful the idea of "building your own," and "owning your own" could be. As well, the music was amazing. I could see and hear how wonderful musical structures could be built by interacting with a set of rules that you set up in advance. In essence, you were inventing your own improvising ensemble and then guiding them through the changes. Also valuable to see was Sal's temper. A local arts reporter, who I knew slightly, came to interview Sal for one of the local papers. At one point, he asked Sal if he was serious in the music he was doing, or something to that effect. (Like Sal and friends would not have devoted several years of their lives to building this machine, not to mention shlepping it all over the countryside if they weren't "serious.") Sal exploded - "Of course it's serious! What the hell do you think?" And then promptly threw the reporter out. I was impressed - and learned a very profound lesson - don't treat bullshit with anything less than contempt. And let people know when they are, inadvertently or not, spouting said bullshit. This is a skill I must admit that I still haven't fully developed, but it is a skill that I admire a lot. Here are two pictures - one of the Sal-Mar on its own in the SUNY Albany Art Gallery, the other of Sal himself performing at the machine. More information about the Sal-Mar can be found at the following website: http://web.media.mit.edu/~joep/SpectrumWeb/captions/SalMar.html

I kept up with Sal for the rest of his life. Every time I would pass through Urbana, I would visit him, enjoying his company and following the progress of his amazing mind and creativity.

Salvatore Martirano, et al, Sal-Mar Construction, SUNY Albany Art Gallery, 1971

Sal Martirano plays the Sal-Mar. SUNY Albany Art Gallery, 1971

The high point of my undergraduate education has to have been the performance of John Cage and Lejaren Hiller's HPSCHD, for multiple harpsichords, tapes, and slide and film projectors. Cage and Hiller came to Albany in advance, and gave wonderful lectures about the work and the principles behind it, and then we all were dragooned into being the tech crew for this amazing work. I took a number of photographs of the event, of which I only include four here.

The first is an overview of the Art Gallery at SUNY Albany. On the bottom of the balcony can be seen some of the many slide projectors that operated during the piece. In the background, on the floor, George Ritscher, from SUNY Buffalo, prepares some of the many loudspeakers in the sound system.

John Cage and Lejaren Hiller: HPSCHD - 1971 Suny Albany performance - overview of Art Gallery during setup.

This photo shows the delivery of one of the four harpsichords into the gallery. It's a utilitarian photo, but it gives and indication of how much preparation the piece involved.

John Cage and Lejaren Hiller: HPSCHD - 1971 SUNY Albany performance - delivery of harpsichords before performance.

The next picture is of John Cage, facing the camera, and Lejaren Hiller and Neely Bruce, who played one of the harpsichord parts, facing away. The delighted look on Cage's face shows that preparations were going well. I have some photos of the post-HPSCHD party which I might show another time, where the expression on the face of an exhausted Cage shows that the performance did indeed go well.

John Cage, facing camera; Lejaren Hiller, Neely Bruce, facing away from camera; Peter Doell, back near camera. HPSCHD - 1971 - SUNY Albany

The final photo is of the back room to the Art Gallery being set up for the performance. Note the multiple analog tape recorders being prepared. If memory serves me correctly, I believe we used every tape recorder owned by SUNY Albany for this performance. HPSCHD can use up to 50 tape recorders, and although we didn't use that many, I know we had an awful lot of them.

John Cage and Lejaren Hiller: HPSCHD - 1971 SUNY Albany performance - back room setup with lots and lots of tape recorders.

What impressed me most about Cage and Hiller in this performance was their absolute professionalism, competence, and insistence on getting all the details right. The care and precision which they applied to the event was conveyed to everyone, and things went swimmingly. In all these concerts, I saw how real professionals acted, and how they put on elaborate events with a minimum of fuss and a maximum of skill. Now THAT was an education.

The professional contacts we made as a result of all these concerts were invaluable. Many years later, for example, when I was about to embark on performing John Cage's word pieces "Empty Words" and some of the Mesostics, I was able to approach him for coaching on ways of performing the texts. Without the introduction of the manic work sessions involved in putting on HPSCHD, I doubt I would have thought of approaching him like that. And this applied to many of the other folks I met as a result of helping them put on concerts for Joel. For example, one of the people I assisted was the Australian composer / pianist Keith Humble, who would later invite me to come to Australia and teach at La Trobe University. As a strategy for compositional education, the apprenticeship model still strikes me as one of the best.

One of the lessons Joel gave about technology was to look at a new piece of equipment, and once you learned a bit about it, to ask, "Ok, what are the compositional implications of this?" This was a lesson that would be repeated by Kenneth Gaburo, when I moved to San Diego, and that's where the next part of our story begins.